Written by Winlin, Azusachino, Benjamin

When our business workloads exceed streaming-server capacity, we have to balance those workloads. Normally, the problem can be solved by clustering. Clustering is not the only way to solve this problem, though. Sometimes the concept of Load Balancing can be linked to many emerging terms such as Service Discovery, but a LoadBalancer in cloud service is an indispensable requirement for solving the problem. In short, this problem is very complicated, and many people ask me about this frequently. Here I’m going to systematically discuss this issue.

If you already have answers to the questions below and understand mechanisms behind, you may skip this article:

- Does SRS need NGINX, F5 or HAProxy as stream proxy? No, not at all. Who think the above three are needed are misunderstanding how streaming-server balances its loads. However, for HTTPS, we recommend using those proxies. And to reduce IP addresses for external service, we also recommend cloud LoadBalancer.

- How to discover SRS Edge nodes? How to discover Origin nodes? Edge nodes can be found through DNS and HTTP-DNS; Origin nodes should not be directly exposed to Clients for connection.

- What is special about WebRTC in terms of Service Discovery? Due to high CPU consumption, it’s easier to reach the threshold of Load Balancing. In single PeerConnection, streaming traffic changes dynamically, which makes it even harder to balance loads; For mobile devices, UDP switching between networks and IP drifting will introduce more problems.

- Comparing DNS and HTTP-DNS, which one is more suitable for streaming media server’s Service Discovery? The answer is of course HTTP-DNS. Because the load change of a streaming-server is greater than that of a Web server, we have to consider how it will affect the load when 1K more clients are added to both servers.

- Whether Load Balancing should only consider how to lower system load? The foremost target is to lower system load, or prevent the system from crashing; when the load is similar, we should also consider factors like nearby service and cost.

- Whether Load Balancing can be achieved by only adding one layer of server? Normally, a large scale CDN distribution system is layered, despite it is designed following static tree structure or dynamic MESH structure, and streaming capability is increased thanks to layering; meanwhile, we can use REUSEPORT strategy to enable node with more load by multi-processing, without adding layer.

- Whether Load Balancing can only be implemented by Clustering? Clustering is a very fundamental way to increase system capacity. Besides, we could combine business logic and Vhost to achieve system isolation, and diverging business and users via consistent hashing.

Well, let's discuss load and load balancing in detail.

What is Load

Before addressing load balancing, let's define what is load. For a server, load is the consequence of increasing resource consumption, at the time of handling more requests from clients. Such an increase may cause the service to become unavailable when there is a serious imbalance.For example, all clients behave abnormally when CPU reaches 100%.

For streaming servers, load is caused by streaming clients consuming server resources. Load is generally evaluated from following perspectives:

- CPU, the computational resources consumed by the server. In general, we would classify the cases that consume huge amounts of CPU resources as computational-intensive scenarios, whereas the cases that consume large network bandwidth as I/O-intensive scenarios. Most of the time, live streaming is I/O-intensive, hence usually CPU is not the foremost bottleneck. Except in RTC, which is a both I/O- intensive and computational-intensive scenario. This is the main difference.

- Network bandwidth, network bandwidth is consumed when transmitting livestream. As mentioned, live streaming is an I/O-intensive scenario, hence bandwidth becomes a critical bottleneck.

- Disk, when there is no need to record and support HLS, disk is not a critical bottleneck. However, in case of recording and HLS are necessary, disk becomes a very critical bottleneck. Simply because the disk is the slowest. RAM drives are usually introduced to solve disk slowness because RAM is considerably more affordable nowadays.

- RAM is a less consumed resource in streaming servers, relatively speaking. Despite a lot of caches in place, RAM generally doesn't reach the limit before others. Therefore, RAM is also used heavily as Cache in streaming servers to exchange load on other resources. For example, in SRS, when optimizing CPU for live streaming, we use writev to cache and send a lot of data. The idea is to use RAM to trade for lower CPU load.

What are the consequences for high loads? It will directly lead to system issues, such as increased latency, lag, or even denial-of-service. Consequences of overload usually occur in the form of chain events. For example:

- CPU overload, which means the server can't support that many clients, will cause a chain of adverse events. On one hand, it will lead to queue stacking, which consumes a lot of memories. On the other hand, network throughput can't keep up as well, because the clients can't receive the data they need, consequently there is increasing latency and lag. All above issues will keep on adding even more CPU overloads, until the server crashes.

- Network bandwidth, when the system’s bandwidth limit is exceeded, such as the limit of the network card or system queue, all users cannot receive the data they need, and there will be lag. In addition, it will cause the queue to stack. More CPU will be required to process the stacked queue, which in return increases CPU load.

- Disk, if the disk load exceeds limit, system may hang further write operation. On servers that do write operation synchronously, it will lead to streams failing to transfer properly and logs piling up. On servers that do write operations asynchronously, it will lead to asynchronous queues to pile up. Note that SRS is currently writing synchronously and we’re working on enabling asynchronous writing in a multi-threaded fashion.

- RAM, the service process will be killed in case of Out-Of-Memory. RAM load increase is mainly caused by memory leaks, especially when there are many streams. For the sake of simplicity, SRS does not clean up and delete streams, hence worth your attention if there is continuous rising in memory load.

In light of those above, to reduce system load, the first and foremost step is to measure the load, aka focusing on overloads, this is also an issue that needs further clarification.

What is Overload

When the load exceeds the system’s load capacity, overload happens. This is actually a complicated issue despite its simplistic description, for instance:

- Whether the CPU consumption reaches 100% means overload happens? No, because generally a server has multiple CPUs, hence a server with 8 CPUs reaches its CPU load limit when CPU consumption is 800%.

- Whether the CPU capacity will not be reached when the CPU consumption rate is below server’s capacity (such as 8-CPU server not reaching 800%)? No, because streaming servers might not use multiple CPU cores. For example, SRS server only uses one CPU, and its CPU capacity is 100%.

- Whether SRS server will not overload when SRS server CPU consumption rate does not reach 100%? No, because other processes also use CPU, SRS is not the only load that consumes CPU resources.

In conclusion, for CPU load and capacity, to know when overload happens, both streaming server’s available CPU resource and CPU resource in use must be identified and measured:

- For system total CPU resources, when the consumption rate reaches 80%, overload happens. For instance, an 8-CPU server, when CPU consumption rate reaches 640%, overload happens. Generally speaking, the total CPU load level is high when a system is busy. .

- For each SRS process, when CPU load reaches 80%, overload happens. For instance, an 8-CPU server total CPU usage reaches 120%, but SRS process only uses 80% of the CPU, other processes consume 40%, it is also overloaded.

Network bandwidth, whether it is overloaded, is considered over the following criteria. Streaming media bandwidth consumption is mainly due to code rate represented as Kbps or Mbps, which stands for bitrate or how much data is transmitted every second.

- One criteria is if server throughput is exceeded. For instance, when a cloud server public network throughput is 10Mbps, and each live stream’s average bitrate is 1Mbps, then the system overloads when there are 10 clients. If there are 100 clients publishing or viewing streams, each client can only transmit 100Kbps of data, consequently it results in severe latency and lag.

- Another criteria is whether the CPU's queue limit is exceeded. In UDP, the maximum size of a system queue is 256KB by default. In case there are many streams, the number and size of streaming packets might exceed the queue size. This will lead to packet loss even when the server throughput is not exceeded. More details can be seen at [performance optimization: RTC] (https://www.jianshu.com/p/6d4a89359352)

- The final criteria is the client's network throughput. Sometimes it is the poor network connectivity on the client side that results in client’s network throughput overload. Especially for live streams, the publisher’s upload throughput is the most important aspect to pay attention to. Some inexperienced publishers might have poor network connectivity, which leads to everyone lagging.

Disk, related to video recording, log splitting and STW problems caused by a slow disk :

- When there are multiple streams that require recording, disk will become the most critical bottleneck since it’s the slowest device. When designing a system, consideration must be given to address such problems. For example, a server has 64GB RAM. 32GB of RAM can be allocated to streaming service as temporary storage for media files. Another solution when having a small disk, is to use external services such as nodejs, with multithreading enabled, and then copy or store the files to the cloud storage. Please refer to Oryx for the best practices.

- Server logs, abnormal situations might lead to large quantities of writing operations to log files. If not being divided and rotated properly, the size of log files will gradually increase, and eventually take up the entire disk space. SRS supports log-rotate, and docker allows setup with log-rotate too. The logs are usually extracted (the entire raw log can be extracted if there is not much), and sent to cloud-hosted log service for analysis. Local logs are only kept for a short period, e.g. 15 days.

- STW (Stop The World) issue. The write operations cause congestion and other disk operations are queued until the write operation completes. Especially when a network disk, such as a NAS, is mounted as a local drive. Then when the server performs data write operations, there are in fact many operations happening at the network layer, which consequently causes more delay. SRS servers should avoid using network disks completely, because each congestion will lead to a STW situation on a server and all other requests will be queued.

As for RAM, the main concerns are leakage and buffering. This is relatively simple, as can be solved by focusing on monitoring RAM usage for a system.

Special for Media Server

In addition to general resource consumption, there are some additional factors that affect load or load balancing in a streaming server, including:

- Long connection: The live streaming and WebRTC streaming are both long. The longest live streaming may exceed 2 days. It's also common to have a meeting that lasts for a few hours. Therefore, the load of the streaming media servers has the characteristics of long connection, which will cause great disturbance to the load rebalancing. For example, the round-robin scheduling strategy may not be the most effective one.

- Stateful: There are many interactions between a streaming media server and its clients. There are some interim states, which makes the load balancing server unable to directly pass the request to a new server when there is a problem with the service, sometimes not even a request. The problem is especially evident in WebRTC, where DTLS and SRTP encrypt these states, making it impossible to switch servers at will.

- Correlation: There is no correlation between two web requests, and the failure of one will not affect the other. While in the live streaming, the push stream can affect all the playback. In WebRTC, the meeting may not continue, as long as one person fails to pull the stream or the transmission quality is too bad, even though the other streams are stable.

These are certainly not completely load and load balancing problems. For example, in order to solve the problem of some weak clients, WebRTC developed SVC and Simulcast. Some problems can be solved by the client's failed retry, such as the server can be forced to shut down when under high load, and then the clients will retry and migrate to the next server.

There is also a tendency to avoid streaming services and insteadly use slices such as HLS/DASH/CMAF, which then served via a web server and all of the above problems become irrelevant. However, the slicing protocol can actually only achieve 3 seconds delay at best, commonly more than 5 seconds. It is impractical to count on a slice server to accommodate 1 to 3 seconds delay, or even achieve the 500ms to 1 second low-latency in the live streaming, the RTC of 200ms to 500ms calls, and control scenarios within 100ms. These scenarios can only be implemented using a stream server, regardless of whether the TCP stream or UDP packet is transmitted.

We need to consider these issues when designing the system. For example, WebRTC should try to avoid coupling between streams and rooms, that is, the streams in a room must be distributed to multiple servers, rather than limited to one server. The more restrictions on these services, the more unfavorable it is for load balancing.

SRS Overload

Let's talk about the load and overload conditions in SRS:

- SRS’s process. When the CPU usage exceeds 100%, overload happens. SRS has a single-process design, hence it cannot take advantage of multiple CPUs (which will be elaborated in the later section).

- Network bandwidth. It is usually the first resource that reaches overload. For example, CPU may still have a lot of free source, when the bandwidth throughput reaches 1Gbps in live streaming. RTC is slightly different, as it is computationally intensive too.

- Disk. Except when recording is only needed for very few streams, it is generally necessary to avoid disk usage so as to avoid consequent problems. Instead we could mount RAM-drives, or reduce the number of streams processed by each SRS. Please refer to Oryx for best practices.

- Memory. It is generally less used, but we still care about the number of streams for some specific cases. For example, in case of CCTV monitoring when constant pushing and disconnecting happens, it is necessary to pay continuous attention to the increasing memory consumption by SRS. This issue can be circumvented by Gracefully Quit.

Special note for SRS single-process design. This is actually a choice. It is a trade-off for performance optimization. On one hand, multiprocessing can improve the processing capability. On the other hand, it is at the expense of increasing complexity of the system. Moreover it is hard to evaluate the overall load. For instance, what is an 8-core multiprocessing streaming server’s CPU overload threshold? Is it 640%? No, because the processes are not evenly consuming CPU resources. To even the process-consumption, we must implement process load balancing scheme, which is a more complicated problem.

At present, the single-process design of SRS can adapt to most scenarios. For live streaming, the Edge can use the multi-process REUSEPORT mechanism to listen on the same port to achieve multi-core consumption. RTC can use a certain number of ports. In cloud-native scenarios, using docker to run SRS, and you can also start multiple K8S Pods. These are options that require less effort.

Note: Except for cloud services that are sensitive to budget, opt for customization is always an option, but at the cost of increasing complexity. To the best of my knowledge, several well-known cloud vendors have implemented multi-processed versions based on SRS. We are working together to open source the multiprocessing capability to improve the system load capacity in an affordable complexity range. For details, please refer to Threading #2188.

Now, we understand loads of streaming servers, it's time to think about how to balance those loads.

Round Robin: Simple and Robust

Round Robin is a very simple load balancing strategy: every time a client requests a service, the scheduler finds the next server from the server list and returns to the client:

server = servers[pos++ % servers.length()]

This strategy is more effective if each request is relatively balanced, for example, web requests are generally completed in a short time. In this way, it is very easy to add and delete servers, go online and offline, upgrade and isolate services.

Due to the characteristics of long connections in streaming media, the polling strategy is not useful enough, because some requests may be longer and some are shorter, which will cause load imbalance.Whereas, this strategy still works well if there are only a small number of requests.

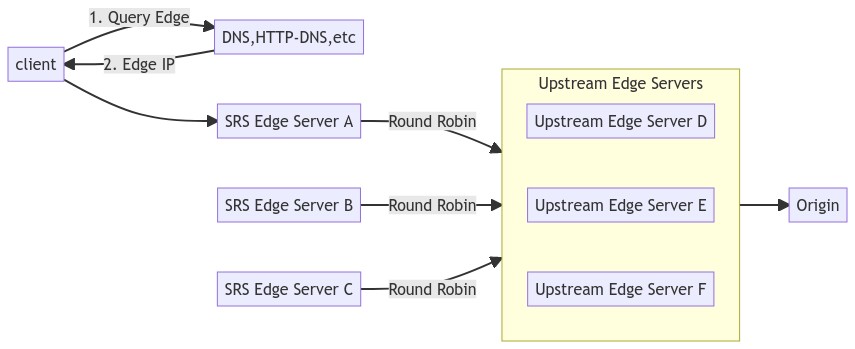

In the Edge Cluster of SRS, the round-robin approach is also used when looking for the upstream Edge servers, with the assumption that the number of streams and the service time are relatively balanced. We consider this is a reasonable and appropriate assumption in open source applications. Essentially, this is the load balancing strategy for the upstream Edge servers, to solve the SRS origin overload problem when all the requests always go back to one server. As shown below:

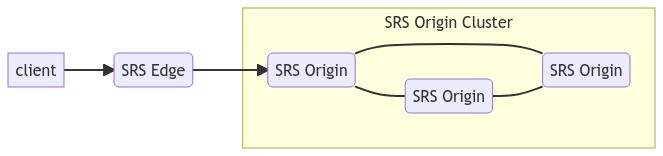

In an SRS Origin Cluster, the Edge will also select an Origin server when pushing the stream for the first time, which uses the Round Robin strategy too. This is essentially the load balancing of the Origin server, which solves the problem of overloading the Origin server. As shown below:

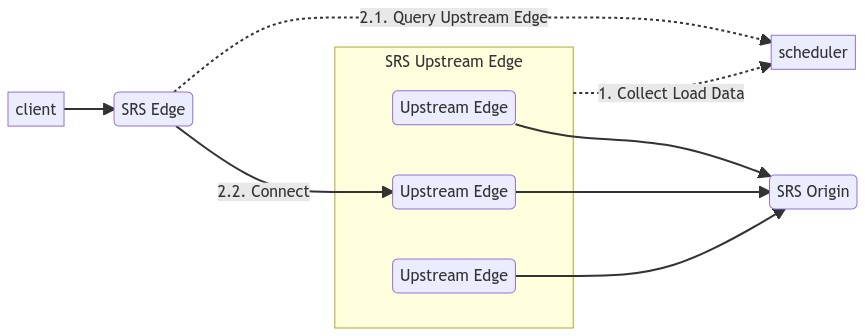

In production business deployment, instead of simply using Round Robin, there is a scheduling service that collects the data from these servers, evaluates the load, and then picks an upstream edge server with lower load or higher service quality. As shown below:

Then how do we solve the load balancing problem of Edge? It relies on the Frontend Load Balancing strategy, which is the system on the frontend access point. We will talk about the commonly used methods below.

Frontend Load Balancer: DNS or HTTP DNS

In the above Round Robin part, we focused on load balancing within the service, while the situation will be a bit different for servers that directly interfaces to the clients, generally called Frontend Load Balancer:

- If the entire streaming service has fewer nodes and is deployed centrally, the Round Robin is an OK choice. Viable options include set multiple resolution IPs in DNS, randomly select nodes when HTTP DNS returns, or select a server with a relatively light load.

- If there are multiple nodes, especially in distributed deployments, it is impossible to choose the Round Robin method, because, in addition to the load, the geographical location of the user also needs to be taken into consideration. Generally speaking, the "nearest" node should be selected. The same can be achieved with DNS and HTTP DNS, which is generally based on the user's exit IP, to obtain geographic location information from the geo-IP database.

In fact, there is no difference between DNS and HTTP DNS in terms of scheduling capabilities, and even lots of DNS and HTTP DNS systems have the same decision-making system, because they have to solve the same problem: how to use user’s IP, and other information (such as RTT or more detection data) to allocate more appropriate nodes. (usually the nearest one, also considering the cost)

DNS is the basis of the Internet. It can be considered as a name translator. For example, when we PING the server of SRS, it resolves ossrs.io into the IP address 182.92.233.108. There is no load balancing capability here, because It's just a server, DNS is just name resolution here:

ping ossrs.io

PING ossrs.io (182.92.233.108): 56 data bytes

64 bytes from 182.92.233.108: icmp_seq=0 ttl=64 time=24.350 ms

What DNS does in streaming media load balancing is actually to return the IP of different servers according to the IP of the client, and the DNS system itself is also distributed. The DNS information can be recorded in the /etc/hosts file. If there is no such information, the IP of this domain name will be queried in LocalDNS (usually configured in the system or obtained automatically).

This means that DNS can withstand very large concurrency, because it is not a centralized DNS server providing resolution services, but a distributed system. This is why there is a TTL and expiration time when creating a new resolution. After modifying the resolution record, it will take effect after this time. In fact, it all depends on the policies of each DNS server, and there are some operations such as DNS hijacking and tampering, which sometimes cause load imbalance.

Therefore, HTTP DNS comes out. It can be considered that DNS is the basic network service provided by ISPs, while HTTP DNS can be implemented by streaming media platforms developers. It is a name service, or you can call an HTTP API to resolve, for example:

curl http://your-http-dns-service/resolve?domain=ossrs.io

{["182.92.233.108"]}

Since this service is provided by yourself, you can decide when to update the meaning of the name. Of course, you can achieve a more precise load-balancing, and also use HTTPS to prevent tampering and hijacking.

Note: The your-http-dns-service of HTTP-DNS can use a set of IP or DNS domain name, because its load is relatively well balanced.

Load Balancing by Vhost

SRS supports Vhost, which is generally used by CDN platforms to isolate multiple customers. Each customer can have its own domain name, such as:

vhost customer.a {

}

vhost customer.b {

}

If users push streams to the same IP server but use different vhosts, then they are different streams. When playback, they are also different streams, with different URL addresses, for example:

rtmp://ip/live/livestream?vhost=customer.artmp://ip/live/livestream?vhost=customer.b

Note: Of course, you can use the DNS system to map the ip to a different domain name, so that you can directly use the domain name in the URL.

In fact, Vhost can also be used for load balancing of multiple origin servers, because in Edge, different customers can be distributed to different origin servers, so that the capabilities of the origin server can be expanded without using Origin Cluster:

vhost customer.a {

cluster {

mode remote;

origin server.a;

}

}

vhost customer.b {

cluster {

mode remote;

origin server.b;

}

}

Different vhosts actually share the same Edge nodes, but Upstream and Origin can be isolated. And, of course, it can also be done with Origin Cluster. At this time, there are multiple origin server centers, which is a bit similar to the goal of Consistent Hash.

Consistent Hash

In the scenario where Vhost isolates users, the configuration file can become much more complicated, and there is a simpler strategy to achieve this job, that is, Consistent Hash.

For example, Hash can be calculated based on the URL of the stream requested by the user, and then used to determine which Upstream or Origin to visit, with which can achieve the same isolation and load reduction.

In practice, there are already such solutions available online, so the scheme is definitely feasible. While, SRS does not implement this capability and you need to implement it by yourself.

In fact, Vhost or Consistent Hash can also be used along with Redirect to accomplish more complex load balancing.

HTTP 302: Redirect

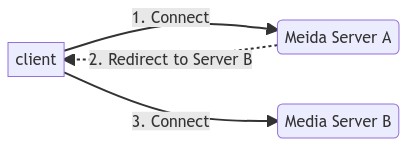

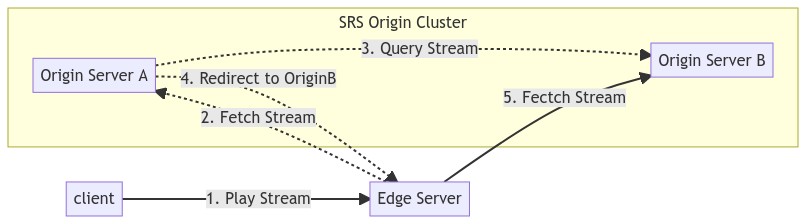

302 is redirect, which can actually be used for load balancing. For example, when access a server through scheduling, but if the server finds that its load is too high, then it can redirect the request to another server, as shown in the following figure:

Note: Not only HTTP supports 302, RTMP also supports 302, and the SRS Origin Cluster is implemented in this way. While 302 here is mainly used for streaming service discovery, not for load balancing.

Since RTMP also supports 302, we can use 302 to achieve load rebalancing within the service. If the load of one Upstream is too high, the stream will be scheduled to other nodes with several 302 jumps.

Generally speaking, in Frontend Server, only HTTP streams support 302, such as HTTP-FLV or HLS. RTMP requires 302 support on the client side, which is infeasible because it is generally not supported.

In addition, UDP-based streaming media protocols also support 302, such as RTMFP (a Flash P2P protocol designed by Adobe), which also supports 302. And it's rarely used now.

WebRTC currently does not have a 302 mechanism, and generally relies on the proxy of Frontend Server to achieve load balancing of subsequent servers. QUIC as a future HTTP/3 standard, will definitely support the basic features like 302. WebRTC will gradually support WebTransport (based on QUIC), so this capability will also be available in the future.

SRS: Edge Cluster

SRS Edge is essentially a Frontend Server and solves the following problems:

- Expand the capability of live streaming, such as supporting 100k viewers, we can scale the Edge Server horizontally.

- Solve the problem of nearby services, which plays the same role as CDN, and is generally deployed in the city where users are located.

- Edge uses the

Round Robinwhen connected to the Upstream Edge to achieve Upstream's load balancing. - The load balancing of Edge itself relies on a scheduling system, such as DNS or HTTP-DNS.

As shown below:

Special Note:

- Edge is an edge cluster for live streaming that supports RTMP and HTTP-FLV protocols.

- Edge does not support slices such as HLS or DASH, slices should be distributed by using Nginx or ATS.

- WebRTC is not supported, WebRTC has its own clustering mechanism.

Since Edge itself is a Frontend Server, it is generally not necessary to place Nginx or other LB in front of it in order to increase system capacity, because Edge itself is to solve the capacity problem, and only Edge can solve the problem of merging back to the origin.

Note: Merging back to the origin means that the same stream will only be returned to the origin once. For example, if 1000 players are connected to the Edge, the Edge will only get 1 stream from the Upstream, rather than 1000 streams. This is different from the transparent Proxy.

Of course, sometimes we still need to place Nginx or LB in front, for example:

- In order to support HTTPS-FLV or HTTPS-API. Nginx is better and supports HTTP/2.

- Reduce external IP. For example, multiple servers only use one IP externally. At this time, a dedicated LB service is required to proxy multiple backend Edges.

- Deploying on the cloud can only provide services through LB, which is limited by the design of cloud products, such as K8S's Service.

In addition, no other servers should be placed in front of Edge, and services should be provided directly by Edge.

SRS: Origin Cluster

SRS Origin Cluster, different from the Edge Cluster, is mainly to expand the origin server’s capability:

- If there are massive streams, such as 10k streams, then a single origin server cannot handle it, and we need multiple origin servers to form a cluster.

- To solve the single-point problem of the origin server, we could switch to other regions when a problem occurs in any region if there are multi-region deployments.

- The performance problem of the slicing protocol, due to the large performance loss while writing to the disk, we could also use multiple origin servers to reduce the load in addition to using the RAM drives.

The SRS Origin Cluster should not be accessed directly and relies on Edge Cluster to provide external services, because two simple strategies:

- For stream discovery, the Origin Cluster will access an HTTP address to query stream, which is configured as another origin server by default, and could also be configured as a specialized service.

- RTMP 302 redirection, if the stream is not on the current origin server, it will be redirected to another origin server.

Note: In fact, Edge could also access the stream query service before accessing the origin server, and initiate the connection after finding the one within the stream. But it's possible that the stream will be switched away, so there still requires a process of relocating the stream.

The whole process is quite simple, as shown below:

Since the stream is always on only one origin server, the HLS slice will also be generated by one origin without extra synchronization. Generally we could use shared storage, or use on_hls to send slices to the cloud storage.

Note: Another way to achieve this: use the dual-stream hot backup. Usually there are two different streams, and we need to implement the backup mechanism. Generally this is very complicated for HLS, SRT and WebRTC. SRS does not support it.

From the aspect of load balancing, the origin cluster fits the job as a scheduler.

- Use

Round Robinwhen the Edge returns to the origin server - Query the specialized service of which origin server should be used

- Actively disconnect the stream when the load of the origin server is too high and force the client to re-push to achieve load balance

SRS: WebRTC Cascade

The load of WebRTC is only on the origin servers. Load balancing at the edge has little relevance in WebRTC service model, because the ratio of publishing to viewing a stream in WebRTC is close to one, rather than the 1-to-10k difference in the live-streaming scenario. In other words, the edge is to solve the problem of massive viewing, and there is no need for load balancing at the edge when the publishing and viewing are similar (in the live-streaming scenario you can use edge for access and redirect).

Since WebRTC does not implement 302 redirect, there is no need to deploy edge (for access). For example, in a common Load Balancing scenario, when there are 10 SRS origin servers behind a VIP (i.e., the same VIP will be returned to the client), which SRS origin server will the client end up with? The answer is that it entirely depends on the Load Balancing strategy. At this time, it is impossible to add an edge to implement the RTMP 302 redirect like in the live-streaming scenario.

Therefore, the load balancing of WebRTC cannot be solved by Edge at all, whereas it relies on the Origin Cluster. Generally speaking, in RTC, this is called Cascade, that is, all nodes are equal, but connected with different levels of Routing to increase the load capacity. As shown below:

This is an essential difference from the Origin Cluster. There is no media transmission between servers in the Origin Cluster, and RTMP 302 is used to instruct Edge redirecting to a specified origin server. The load of the origin server is predictable and manageable, as one origin server only owns a limited number of Edges.

The Origin Cluster strategy is not suitable for WebRTC, because the client needs to connect directly to the origin server, and then the load of the origin server is not manageable at this time. For example, in a conference of 100 people, each stream will be subscribed by 100 people. At this time, users are distributedly connected to different origin servers. Hence, establishing connections among all the origin servers is required, in order to push one's own stream and get others’.

Note: This example is a rather rare case. Generally speaking, a 100-person interactive conference will use the MCU mode, in which the server will merge different streams into one, or selectively forward several streams. The internal logic of such a server is very complicated.

In fact, one-to-one call is considered as the common WebRTC scenario, which accounts for about 80% of the business case. At this time, everyone publishes one stream and plays one stream. In a typical situation when there are many streams, the user can just connect to one origin server nearby. While the geographical locations of the users might not be the same, such as in different regions or countries, then the cascade between the origin servers should improve call quality.

Under the cascading architecture of origin servers, users access HTTPS API using DNS or HTTP DNS protocol. The IP of origin server is returned in SDP, so this is an opportunity for load balancing, which can return an origin server that is close to the user and has less load.

In addition, how to cascade multiple origin servers? If users are in a similar region, they can be dispatched to one origin server to avoid cascading. It saves internal transmission bandwidth (it is a well worthy and effective optimization when there are a large number of one-to-one calls in the same area). At the same time, this also increases the un-schedulability of loads, especially when a conference evolves into a multi-person one.

Therefore, in a conference, distinguishing one-to-one from multi-person conferences, or limiting the number of participants in it is actually very helpful for load balancing. It's easier to schedule and achieve load-balance if you are aware this is a one-to-one conference ahead of time. Unfortunately, project managers are generally not interested in this opinion.

Remark: Note that the cascading feature has yet been implemented in SRS. Only the prototype has been implemented, and it has not been committed to the repository.

TURN, ICE, QUIC, etc

In particular, let's talk about some WebRTC-related protocols, such as TURN, ICE, and QUIC.

ICE is not actually a transmission protocol, it is more like an identification protocol, generally referring to Binding Request and Response, which will contain IP and priority information to identify the address and channel information for the selection of multiple channels, such as Who to choose when both 4G and WiFi are good enough. It is also used as the heartbeat of the session, and the client will always send ICE messages.

Therefore, ICE has no effect on load balancing, but it can be used to identify sessions, similar to QUIC's ConnectionID, so it can play a role in identifying sessions when passing through Load Balancing, especially when the client's network switches.

The TURN protocol is actually a very unfriendly protocol for Cloud Native, because it needs to allocate a series of ports and use ports to distinguish users. This is practical in private networks, assuming that the ports are unlimited, while the ports on the cloud are often limited.

Note: Of course, TURN can also multiplex a port without actually assigning a port, which limits the ability to use TURN to communicate directly but go through SFU, and there is no problem with SRS.

The real deal of TURN is to downgrade to the TCP protocol, because some enterprise firewalls do not support UDP, so they can only use TCP, and the client needs to use the TCP function of TURN. Of course, you can also use the TCP host directly. For example, mediasoup supports it already, but SRS doesn't support it yet.

The 0RTT connection in QUIC is more friendly. The client caches the SSL ticket-like thing and can skip the handshake. For load balancing, QUIC is more effective because it has a ConnectionID. Then, when load balancing, even though the client changes the address and network, Load Balancer can still know which service on the backend handles it. But, of course, this actually makes the server load more difficult to transfer.

In fact, such a complex set of protocols and systems as WebRTC is quite messy and disgusting. Since the 100ms-level delay is a hard indicator, UDP and a complex set of congestion control protocols must be used, and encryption is also indispensable. Some people claim that Cloud Native's RTC is the future, which introduces more problems like port multiplexing, load balancing, long-connection and restart upgrades, as well as the structure that has been turned upside down, and HTTP/3 and QUIC to spoil the game...

Perhaps for the load balancing of WebRTC, there is one word that is most applicable: there is no difficulty in the world, as long as you are willing to give up.

SRS: Prometheus Exporter

The premise for Load Balancing is to know how to balance the load, which highly depends on data collection and calculation. Prometheus is for this purpose. It will continuously collect various data, and calculate these data according to its set of rules. Prometheus is essentially a time series database.

System load, which is also essentially a series of time series data, changes over time.

For example, Prometheus has a node_exporter, which provides the relevant timing information of the host node, such as CPU, disk, network, memory, etc., which can be used to compute service load.

Many services own a corresponding exporter. For example, redis_exporter collects Redis load data, nginx-exporter collects Nginx load data.

At present, SRS has not implemented its own srs-exporter, but it will be implemented in the future. For details, please refer to #2899.

Cloud Service

At SRS, our goal is to establish a non-profit, open-source community dedicated to creating an all-in-one, out-of-the-box, open-source video solution for live streaming and WebRTC online services.

Additionally, we offer a Cloud service for those who prefer to use cloud service instead of building from scratch. Our cloud service features global network acceleration, enhanced congestion control algorithms, client SDKs for all platforms, and some free quota.

To learn more about our cloud service, click here.

Contact

Welcome for more discussion at discord.